The retail apocalypse has already happened many years back. Are we going through a post-apocalypse rebuild now? Let’s explore how the consumer-direct model and small boutique brands have been able to thrive in this retail post-apocalypse.

This thought piece examines the big question through the (goggle) lens of a fanatical mountain biker (yours truly) who has been part of the sport for over a decade. I have spent my younger days at a traditional brick-and-mortar bike shop and seen it shutter down as well. The mountain biking industry is not new to unprecedented changes, from consumer adoption of

wireless electronics that control shifting to new industry standards being set yearly. Just imagine if your car goes out of date every two years. Bummer.

Pre-Apocalypse: Brick-and-Mortar Retailers

In the past, brick-and-mortar stores were the norm. Distributors sold products at wholesale price to retailers, while retailers had to mark it up further to make a sustainable margin.

Your friendly neighbourhood bike shop probably sold entry-level to mid-range bikes, while big brand showrooms in glass facades positioned similarly to automobile dealers. Walk-in human traffic was key.

Over time, shop locations took a gradual shift from high-traffic residential areas to industrial areas. Objectively, this cleaned up the sales funnel as they had less window shoppers ‘taking a look’ without purchasing anything. Customers who made a point to drop by a relatively inaccessible location needed something they could pay for.

The First Disruption: e-commerce Model

We are all familiar with this.

Browse. Add to cart. Checkout.

(From the comfort of your couch!)

Nothing beats the joyful anticipation of your new items on the way. This early wave of the e-commerce model was primarily for component upgrades which could be said to be the lifeblood of the bike industry. New bling makes everyone ride faster with less effort, or at least that’s what we like to think.

Facing issues with stuck inventory, most local bike shops (LBS) adapted by placing a shift away from product sales to servicing:

Because new bling can’t perform like new if you neglect them.

Besides being stuck with inventory, surely, it couldn’t get any worse, right?

The Second Disruption: Consumer-Direct Model

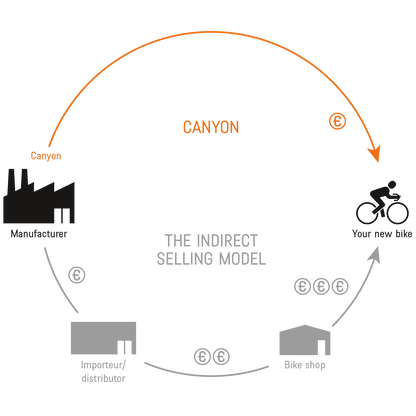

Enter the Consumer-Direct Model (also known as Direct Sale).

German bike brands Canyon and YT were the prominent two pushing this business model. By skipping the middlemen wholesaler and retailers, Canyon and YT were able to deliver more value to the consumer for the same dollar they paid. Needless to say, these brands grew in scale and readily claimed their well-deserved portion of market share from the reknowned ‘Big Three’, namely Trek, Giant and Specialized.

YT stands for Young Talent and they are all about overcoming conventions.

Resistance: Brick-and-Mortar Retailers

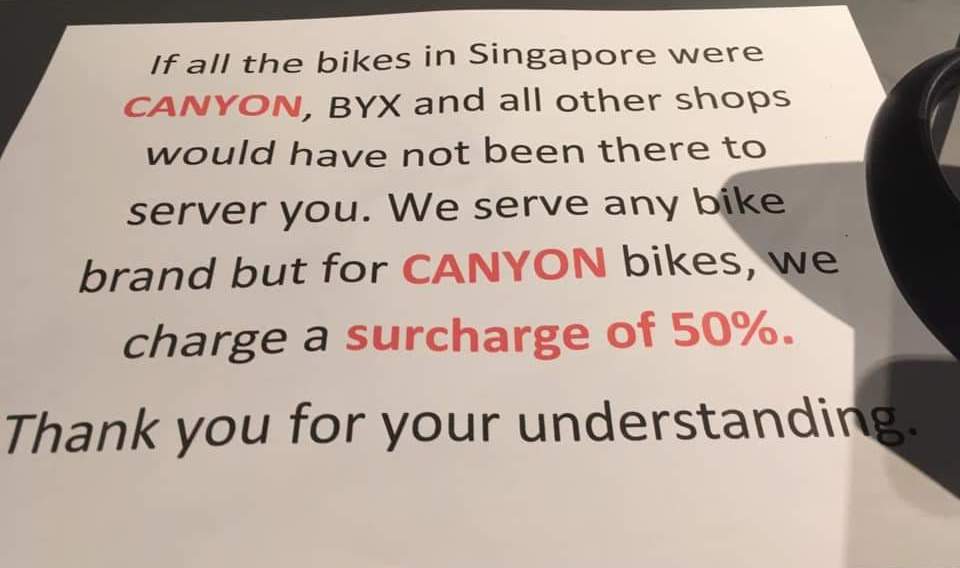

The Consumer-Direct Model effectively made retailers redundant, with local bike shops taking hit. One even took a protectionist approach against consumer-direct brands:

Ouch.

Hybrid Model: Established Brands

A synthesis developed as a response from mass-market, established bike brands that conventionally sold through distributors and numerous retailers. Besides getting on the online store bandwagon, they appointed a limited number of retailers to sell, reinvigorating the brick-and-mortar stores with a level of exclusivity.

If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em!

However, this two-pronged approach was not without downsides. Consumers were unable to enjoy the competitive price that came with direct sales, while bike shop margins had to be thin to compete with the Direct Sale model.

Hybrid Model: Boutique Brands

A prominent boutique bike brand: Evil Bikes.

Boutique mountain bike brands grew much faster with this hybrid model, as opposed to established, mass-market brands. Boutique brands are run by small outfits of passionate mountain bikers, who produce only high-end bikes. One could liken them to local Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs) driven by self-starters.

The Lexus LFA, no longer in production.

We can relate this difference with the automotive industry as an example. Lexus manufactures its LFA supercar, but its main focus is not on supercars.

“It is possible that we will one day create another supercar, but in my view a super-high-end machine is not what we need right now.” – Head of Lexus Europe

Lexus as a luxury division sits under the massive automaker Toyota, which has an extensive range of vehicles and mass production output. Instead, meeting mass-market demand is its priority as a big-name automaker.

1 out of 80 such Koenigsegg Regeras in the world

Compare that with Koenigsegg, a luxury supercar manufacturer with limited production of 80 units for its Regera grand tourer. We can see how exclusivity is a huge factor here. Boutique brands appeal greatly to the consumer segment who want a bespoke product made for them, different from anyone else’s. This mentality differs from mass market consumption and continues to drive the success of a handful boutique brands, such as Kingdom and Guerilla Gravity.

It’s High Time to Thrive

Innovators will always find ways to compete and deliver significantly more value to customers. This is the whole ball game of the free market economy. Even without an economy of scale, the proven success of boutique bike brands exemplifies this:

There is no business too small to challenge its big, established players in this age of disruption.

Additionally, people tend to root for the underdog. Numerous social psychology studies point to this tendency toward supporting those at competitive disadvantage, or new challengers on the playing field. The Singapore government even offers up to 90% grant for growing SMEs to transform their brand and level their playing field.